90 Years Later, the NLRA Faces New Threats to Labor Rights

In July 1935, Congress passed a law that reshaped America’s labor system. The National Labor Relations Act (NLRA), also known as the Wagner Act, laid the foundation for workers’ rights to organize. Backed by New Deal energy, the law introduced protections never seen before. It banned employer interference in union efforts, promoted collective bargaining, and established the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) to enforce workers’ rights.

Ninety years later, that same framework still stands—but barely. While the goals of the Wagner Act remain relevant, its power has weakened, and its structure faces growing challenges from both political and legal fronts.

A Landmark That Sparked a Labor Boom

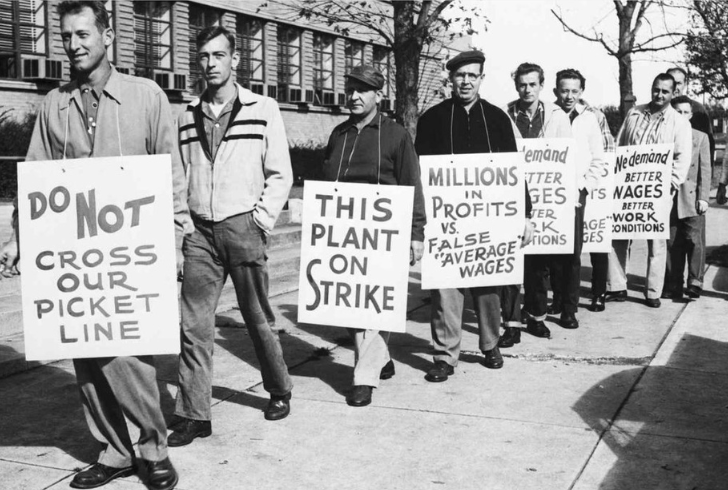

At the time of its passage, the Wagner Act came as a direct response to economic distress and labor unrest. Factory occupations, strikes, and clashes with security forces signaled the urgent need for change. Lawmakers saw collective bargaining not just as a labor issue but as a path to economic recovery.

This law granted workers the right to freely organize and criticize dangerous or unfair working conditions without fear of retaliation. It even empowered those not involved in official union elections to engage in “concerted activity” to push for better treatment.

Instagram | @usinholysee | The Wagner Act’s early impact shows how it helped workers organize and gain real power nationwide.

Union membership exploded in the years that followed. Mass-production industries—from auto to steel—saw rapid union growth, driven by the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO), which expanded worker protections beyond traditional trades. For the first time, many Black and female workers gained union access.

The act even withstood Supreme Court examination in 1937, which was surprising considering the Court’s previous opposition to worker rights. By the early 1950s, union membership had reached one-third of the American workforce.

The Decline of Union Power

Fast forward to today, the reality looks different. Only 6% of private sector workers belong to unions, marking the lowest rate since 1900. Overall union density, including the public sector, hovers around just 10%.

Much of this decline stems from legal shifts. The 1947 Taft-Hartley Act weakened the original NLRA. Over time, employers adopted aggressive legal strategies to block organizing, often with few consequences.

According to the Economic Policy Institute, these changes severely undercut the law’s power. They point to the dramatic drop in new union formation starting in the 1970s—a trend that continues. With legal support, employers now have an abundance of freedom to oppose union drives.

Rising Challenges From Within and Without

Today’s threats to the NLRA extend beyond corporate boardrooms. Legal and political forces are also circling. A business-aligned coalition called the “Coalition for a Democratic Workplace” has urged Attorney General Pam Biondi to invalidate 15 key NLRB rulings without the usual legal review.

Trump’s recent return to office has accelerated this shift. His administration replaced General Counsel Jennifer Abruzzo—known for pushing pro-worker reforms—and even fired Gwynne Wilcox before her NLRB term ended, a move many legal scholars see as unconstitutional.

This maneuvering may lead the Supreme Court to revisit the long-standing Humphrey’s Executor case. That ruling protects officials at independent agencies from being fired without cause. Overturning it would upend decades of precedent and strip agencies like the NLRB of structural independence.

Scholars and Advocates Speak Out

Legal scholars such as UC Berkeley’s Diana Reddy warn that employers are trying to “relitigate the New Deal.” In pending court cases, some are challenging the very existence of the NLRB’s authority. Their arguments question the board’s judges, remedies, and structural integrity.

Jennifer Abruzzo, now back with the Communications Workers of America (CWA), continues to defend the Wagner Act’s original intent. In recent testimony, she condemned the firing of Wilcox and warned of unchecked employer power in the absence of a functioning NLRB.

“Who benefits from this dysfunction?” she asked. “Not workers, but employers who now feel free to break the law without consequences.”

Reform Promises From Democrats Fall Flat

For decades, Democrats in the White House promised labor reform. Yet major overhauls never materialized. While each president appointed more union-friendly NLRB members, they failed to push structural changes through Congress.

Carter made the strongest attempt in 1977, but a Senate filibuster blocked his plan. Obama supported the Employee Free Choice Act (EFCA), which would have allowed union formation through card-checks, yet he chose to prioritize healthcare reform instead.

Biden’s administration has made headway with pro-labor rules and appointments. Still, real legislative change remains out of reach.

A Long List of Proposed Fixes

The problems with labor law enforcement have been clear for decades. Back in the 1970s, United Mine Workers called for several reforms:

1. Stronger penalties for companies firing organizers

2. Faster reinstatement of dismissed employees by decisions from federal courts

3. Denying federal contracts to lawbreaking firms

4. Tougher sanctions against companies that bargain in bad faith

5. Allowing new unions through majority card signatures instead of drawn-out NLRB elections

Today, those recommendations are still relevant. Yet the legal landscape favors employers more than ever.

The PRO Act Stalls While “Right to Work” Rules Expand

The PRO Act, an ambitious plan that addresses current labor challenges, is being supported by Congressional Democrats. It contains clauses to repeal “right to work” laws, which permit employees to avoid paying union dues even in cases where they are covered by a union contract.

Still, the political support behind it remains weak. In Colorado, for instance, a Democrat-controlled legislature passed a repeal of the state’s right-to-work law, only to have Democratic Governor Jared Polis veto it. Unions there now plan to take the issue directly to voters.

A New Era of Union Organizing Outside the NLRB

Instagram | @uaw.union | Unions find new success as more companies like Microsoft support organizing without elections.

While the NLRB remains gridlocked, many unions are bypassing it entirely. They’re targeting companies willing to voluntarily recognize unions through card-check agreements. These efforts often work better than drawn-out elections vulnerable to employer interference.

Some recent wins stand out. Volkswagen accepted a union at its Chattanooga plant without legal battle. And Microsoft agreed to remain neutral during organizing at Activision Blizzard, helping game developers at ZeniMax secure a union without holding an election.

ZeniMax workers went on to sign their first contract in June after voting to strike. According to Microsoft Vice President Amy Pannoni, the agreement shows the company’s “commitment to employee voice and collaborative labor relations.” Such statements echo New Deal values, but today, they remain rare.

What’s Next for the Wagner Act?

Although the Wagner Act is still in force, it no longer reflects the power it once carried. Most union victories today happen outside the structure it created. Employers routinely exploit legal loopholes, while federal efforts to close them have stalled.

Yet even now, workers continue to fight. Whether through legislative pushes like the PRO Act or direct action like ZeniMax’s union campaign, labor is searching for new ways to restore balance. In some corners of the economy, especially in tech and service industries, these approaches show promise.

Still, the future of collective bargaining depends on more than hopeful organizing. It also requires legal enforcement, political will, and sustained worker activism.

As the Wagner Act turns 90, its legacy hangs in the balance. While it sparked historic gains, today’s political and legal challenges demand more than nostalgia. Labor’s next chapter will depend on bold reform, creative organizing, and the determination to push forward—even when the system resists.